Strait of Magellan : Legendary passage between the oceans

Association Karukinka

Loi 1901 - d'intérêt général

Derniers articles

Suivez nous

At the heart of Chilean Patagonia stretches one of the planet’s most emblematic sea passages: the Strait of Magellan. This 570-kilometre natural waterway, separating continental Patagonia from Tierra del Fuego, forms the main bi-oceanic corridor linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Inhabited for millennia by the Selknam, Kawésqar and Tehuelche peoples and discovered more than 500 years ago by Ferdinand Magellan, this strategic passage continues to fascinate thanks to its exceptional history, unique geography and remarkable biodiversity.

Table des matières

History and European discovery: in the footsteps of Magellan

The historic expedition of 1520

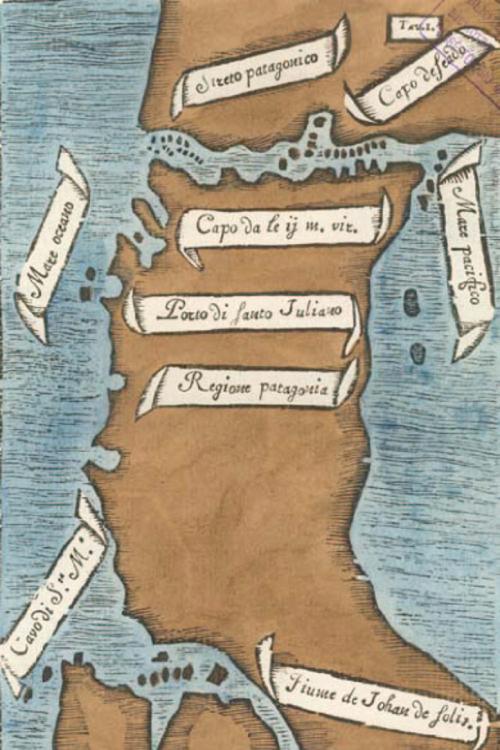

October 21, 1520, marks a crucial date in the history of global navigation. On this day, the Spanish expedition led by the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan discovered the eastern entrance of the strait that would bear his name. Departing from Seville in September 1519 with five ships and 237 men, Magellan was searching for a passage to the Molucca.

The explorer initially named the passage “Estrecho de Todos los Santos” (“Strait of All Saints”) in reference to the religious feast celebrated on the day of its discovery. It was only after his death in the Philippines that Charles V, King of Spain, renamed the strait in honor of its discoverer.

A perilous and revolutionary navigation

Crossing the strait proved particularly difficult for Magellan’s expedition. The sailors faced violent winds, unpredictable currents, and a maze of channels bordered by snow-capped mountains. Antonio Pigafetta, the expedition’s chronicler, described the passage as being “110 leagues long” (about 440 miles) with “very safe harbors, excellent waters, cedar wood

This discovery revolutionized global navigation by providing an alternative to the treacherous Cape Horn passage. Numerous expeditions were conducted to advance hydrographic knowledge to improve navigation safety; among these was the Beauchesne expedition. Before the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, the Strait of Magellan quickly became the main maritime route connecting Europe to the Pacific coasts of the Americas.

Geography and physical characteristics

Dimensions and configuration

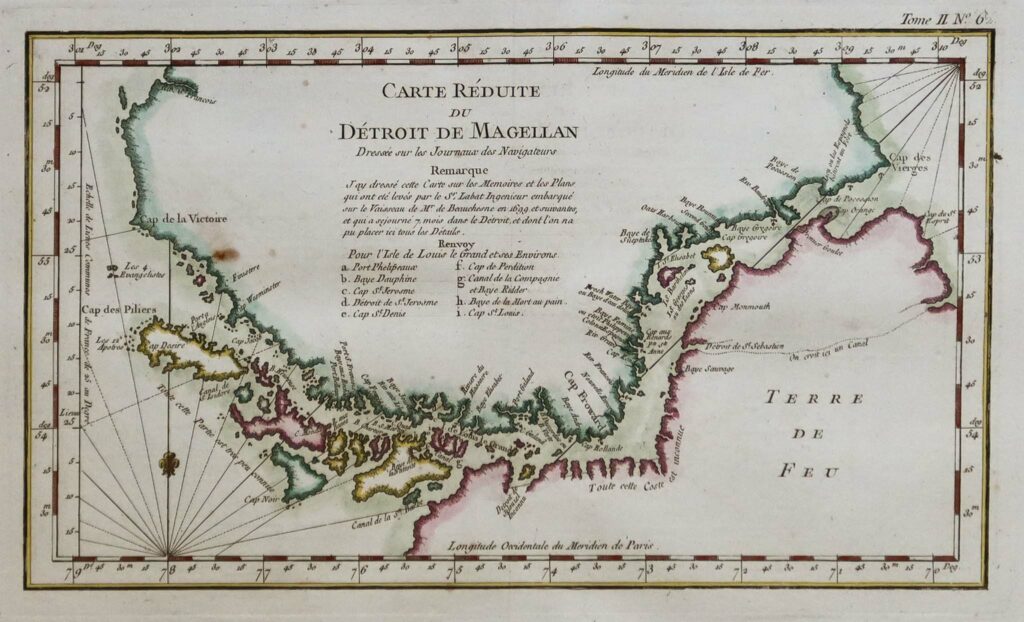

The Strait of Magellan stretches 570 kilometers from Punta Dungeness in the east to the Evangelistas islets in the west. Its width varies greatly: it narrows to just 2 kilometers at its narrowest point near Carlos III Island and can widen to 32

The strait’s depths are remarkable, ranging from a minimum of 28 meters near Magdalena Island to a maximum of 1,080 meters at the Cooper Key lighthouse. This complex geological configuration is the result of millions of years of tectonic and glacial activity that have shaped the Patagonian landscape.

Geological formation

The strait’s origin dates back to the Late Cretaceous, about 80 million years ago. Earth movements created fractures with flat walls, giving rise to the Patagonian channels. During the Pleistocene, 1.5 million years ago, glacial action (glacial geology) deepened and widened these natural passages.

This geological history explains the strait’s unique morphology, characterized by deep fjords, rocky islands, and winding channels forming a true maritime labyrinth.

Climate and navigation conditions

This historic maritime passage poses particularly challenging weather conditions for navigation. The sub-antarctic climate features persistent westerly winds, often called “williwaw” (a Kawésqar word), which can exceed speeds of 100 knots (185km/h).

These winds, descending from coastal mountains (katabatic winds), create violent and unpredictable gusts, making navigation perilous. Temperatures generally range from -5°C to 15°C, with frequent precipitation and visibility often reduced by fog.

Indigenous Peoples: first guardians of the Strait

Long before Ferdinand Magellan discovered this maritime passage in 1520, the strait and its surroundings had been inhabited for over 11,000 years by different indigenous peoples. These first inhabitants developed complex and diverse cultures, perfectly adapted to the extreme conditions of southern Patagonia. Three main ethnic groups coexisted in this region: the Kawésqar, the Tehuelche (Aónikenk), and the Selknam.

These natives peoples had a deep knowledge of the land and were already navigating these difficult waters centuries before the arrival of Europeans. It was, in fact, their campfires, seen by Magellan’s expedition, that gave the name “Tierra del Fuego” (“Land of Fire”).

Before being called the “Strait of Magellan” and as part of indigenous cartography reconstruction activities by the Karukinka association, one Selknam transcription for this passage between the continent and Tierra del Fuego is Hatitelen.

The Kawésqar: nomads of the channels

The Kawésqar or Kawashkar, also incorrectly called Alacalufs by European navigators, are one of the peoples of the Patagonian channels. Sea nomads, they traveled the channels and fjords between the Gulf of Penas and the Strait of Magellan by canoe for about 6,000 years.

Lifestyle and territory

The Kawésqar territory covered a vast area, including the western part of the strait, Wellington Island, Santa Inés Island, and Desolación Island. Exceptional navigators, they lived mainly on their boats—canoes built from tree bark allowing movement through the Patagonian channel labyrinth.

Their society was organized into small family groups constantly moving in search of marine resources. They fed mainly on sea lions, shellfish, fish, and also collected cholgas (giant mussels up to 17cm). Their name literally means “person” or “human being” in their language.

Spirituality and rituals

The Kawésqar had a belief system centered on Xólas, an omnipresent and celestial creator being. Their complex rituals included ceremonies where women assembled in specialized huts, with their bodies painted, to commune with spiritual forces.

The use of body paint was central to their culture, especially during religious ceremonies and initiation rituals. These practices reflected a sophisticated worldview adapted to their extreme maritime environment.

The Tehuelche (Aónikenk): giants of the continental steppe

The Aónikenk, the southernmost branch of the Tehuelche group, inhabited the vast Patagonian steppes between the Santa Cruz River and the Magellanic strait. These nomadic hunter-gatherers were the first indigenous people encountered by Magellan’s expedition in 1520.

The “Patagonian Giants”

European navigators were amazed by the imposing stature of the Aónikenk, who generally measured over 1.80 meters, quite remarkable compared to Europeans of the time (under 1.65 meters). This physical difference gave rise to the myth of the “Patagonian giants” and the very name Patagonia.

The term “Patagón” was coined by Antonio Pigafetta, referring to the giant Pathoagon, a character from a chivalric novel, thus captivating the European imagination. The Aónikenk called themselves “aonek’enk,” meaning “people of the south.”

Social organization and territory

Aónikenk society was fundamentally egalitarian, organized in bands of hunter-gatherers who moved on foot across their hunting grounds. They possessed detailed environmental knowledge and set up their camps (aike) in strategic places.

Their territory was divided into family hunting zones with clearly established boundaries. Transgressing these could cause conflicts, highlighting the importance of spatial organization in their society.

The Selknam: guardians of Tierra del Fuego

The Selknam, also called Onas by their Yagan neighbors, inhabited the large island of Tierra del Fuego and represented one of the region’s most sophisticated cultures. They arrived on the island on foot before the end of the last glaciation, when the strait was still closed by ice, and developed a complex society with elaborate rituals.

Territorial and social organization

Selknam society was structured around lineages inhabiting communal territories called haruwen. The island was divided into several such territories, grouped into seven “cielos” (skies), major exogamous divisions requiring members to marry those from other groups.

This complex organization revealed a highly stratified society where every natural element was associated with mythical ancestors and specific spiritual territories.

The Hain ceremony

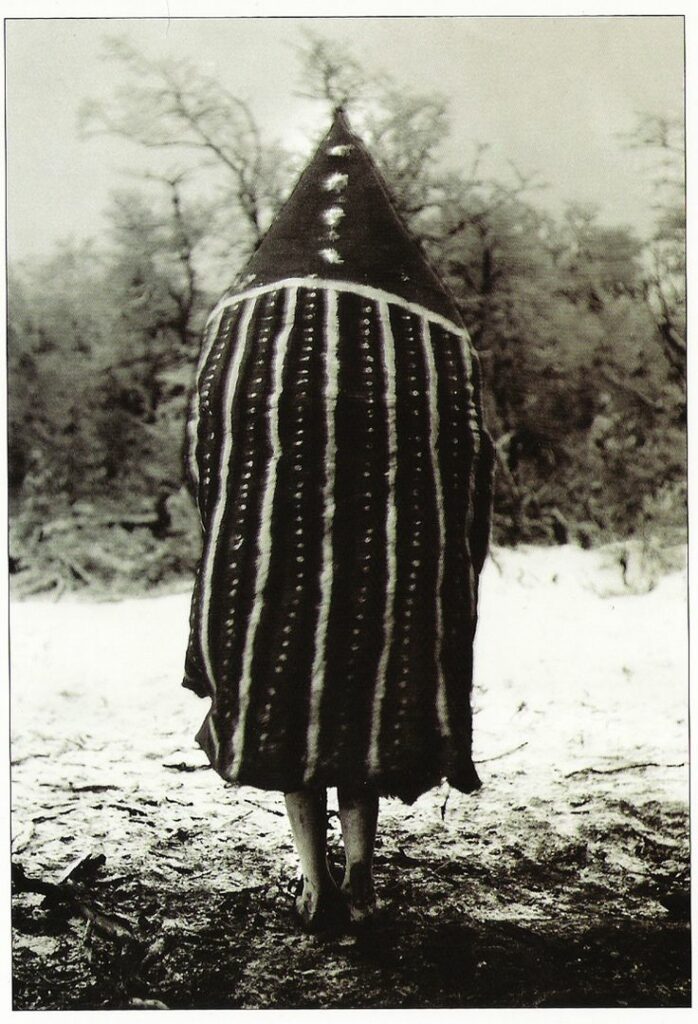

The most remarkable Selknam ritual was the Hain ceremony, a complex male initiation that could last several months. It served to initiate young men into adulthood while maintaining male dominance through sophisticated theatrical performance.

During the Hain, adult men disguised themselves as spirits using elaborate body paintings and masks, terrifying women who had to believe in these supernatural manifestations. The Selknam used only three colors: black (charcoal and ash), white (white clay), and red (ochre).

Shamanism and spirituality

Selknam shamans, called xo’on, enjoyed great prestige. They entered trances through extended chants, their souls attempting to ascend to one of the “skies” to obtain spiritual power. These shamanic practices reflected a complex spirituality connected to their territorial worldview.

Impact of colonisation and genocide

The arrival of European colonization in the 19th century marked the start of an unprecedented human tragedy for these peoples. Chilean and Argentinian colonization, with the establishment of sheep ranches and whaling, unleashed a true genocide against indigenous populations.

Systematic extermination

Between 1870 and 1900, Chilean and Argentinian authorities organized extermination campaigns against Patagonian and Fuegian peoples. Ranchers paid bounties for the ears of killed natives, making manhunt a profitable activity.

The Selknam population, estimated at over 3,000 in 1896, dropped dramatically to 279 in 1919 (Martin Gusinde, ethnologist), then to just 25 in 1945 (official figures). These numbers must be treated with caution, as they reflect the period’s filters, including intermixing and the need to hide indigenous identity for self-protection.

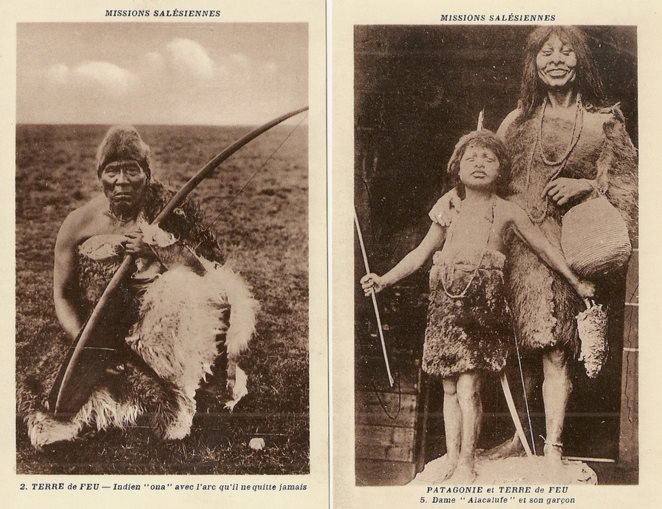

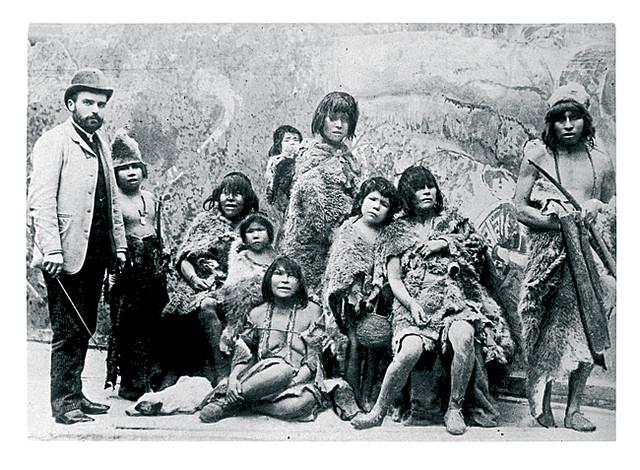

Human exhibitions

Humiliation culminated with the exhibition of native groups in European and South American “human zoos.” From 1878 to 1900, representatives of the Tehuelche, Selknam, and Kawésqar were captured to be displayed as curiosities. Many did not survive these dehumanizing exhibitions, some of the most degrading manifestations of colonialism and foundational acts of racism.

Renaissance and contemporary recognition

Despite assassination attempts, these peoples are not extinct. In recent decades, a remarkable cultural and political revival has taken place.

Official recognition

Argentina officially recognized the Selknam in 1994, while Chile did so in 2023 through Law 21,606. The 2010 Argentinian census records 2,761 people identifying as Selknam, with over 294 living in Tierra del Fuego. In Chile, 1,144 people declared themselves Selknam in the 2017 census.

The Kawésqar are recognized by Chilean Indigenous Law 19,253 (since 1993) and are organized into 14 Indigenous Communities. According to the 2017 Chilean census, 3,448 people declare themselves Kawésqar.

Research and rehabilitation

Chilean universities, notably the Universidad de Magallanes and the Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez, conduct research to document the true history of these peoples. Their findings show the Selknam were more numerous than previously thought and challenge colonizer-imposed historical narratives.

This cultural revival bears witness to these peoples’ extraordinary resilience, who, despite systematic genocide, keep their identity alive and claim their place in the history of the Strait of Magellan.

Patagonia wildlife : an exceptional marine fauna

The Strait of Magellan harbors remarkable marine biodiversity, ranking among the richest areas of the Southern Hemisphere. Its cold, nutrient-rich waters support a unique ecosystem with numerous endemic species.

Magellanic penguins

Magdalena Island, 32km northeast of Punta Arenas, hosts the strait’s largest Magellanic penguins colony (Spheniscus magellanicus) colony—about 50,000 breeding pairs gather there each year (October to March) for the breeding season.

Named in honor of Ferdinand Magellan, who saw them in 1520, these penguins reach up to 76cm and weigh 2.7–6.5kg, and are distinguished by two characteristic black bands on their chest.

Marine mammals

The strait supports a rich population of marine mammals. Humpback whales are especially frequent in the Francisco Coloane Marine Protected Area, created for their conservation—one of the world’s best whale-watching spots.

South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens) and southern elephant seals establish colonies on the strait’s rocky islands. Marta Island, near Magdalena, is home to over 1,000 sea lions and various seabird species.

Bird diversity

The strait’s waters attract many seabird species: imperial cormorants, black-browed albatrosses, southern giant petrels, and the majestic Andean condors.

Terrestrial flora and coastal ecosystems

Coastal vegetation from the strait to Cape Horn reflects the flora’s remarkable adaptation to Patagonia’s extreme climate. Nothofagus forests—Magellan’s beech (Nothofagus betuloides), lenga (Nothofagus pumilio), and ñirre (Nothofagus antarctica)—dominate wind-shaped wooded areas.

More exposed zones feature matorrals composed of romerillo (Chiliotrichum diffusum), chaura (Pernettya pumila), and the iconic calafate (Berberis microphylla), a small fruit shrub. The region also boasts an exceptional diversity of mosses and lichens, miniature bryophyte forests emblematic of these subantarctic ecosystems.

Magellan Strait navigation and modern strategic importance

Mandatory piloting and Chilean maritime navigation rules for safety

Since 1978, navigation in the Strait of Magellan, as a cape Horn alternative, has required mandatory piloting for all commercial vessels, a measure by Chilean maritime authorities to ensure safety in these challenging waters and protect the exceptional marine environment.

Pilots generally board at Bahia Posesión for the eastern entrance and guide ships to the western exit near the Evangelistas islets, backed by a network of lighthouses and maritime traffic control stations along the strait.

Economic and geopolitical renaissance

Contrary to pessimistic predictions after the Panama Canal opened, the Strait of Magellan is experiencing a major strategic renaissance. Chilean Navy reports a 25% maritime traffic increase in 2024 over the previous year and projects a 70% increase for the year overall.

This growth results from several converging factors: global geopolitical tensions, the Panama Canal’s limitations for large ships, and Asia-Pacific’s emergence as a global economic hub. The strait route is 390 nautical miles shorter than via Cape Horn, saving about 32 navigation hours.

Green hydrogen development Magallanes

Magallanes is emerging as a major green hydrogen player, thanks to its exceptional climate. Constant, strong winds provide wind energy potential capable of producing seven times Chile’s current electrical capacity.

This controversial development would turn the strait into a strategic energy corridor for global green hydrogen supply. Chinese and Japanese investments reflect growing international interest in this new economic activity.

Tourism and discovery

Cruises and wildlife observation tours

The Strait of Magellan has become a premier tourist destination, attracting nearly 77,691 passengers for the 2024–2025 season. Punta Arenas, the region’s main port, hosts 175 cruises from 47 different ships, establishing the area as Chile’s leading cruise tourism port system.

Excursions to Magdalena Island are the highlight, with half-day trips for visitors to observe Magellanic penguins and whales in their natural habitat, guided by specialists who share insights about the birds’ and whales’ biology and behavior.

Antarctic gateway for tourism

The strait is a preferred gateway to Antarctica: Over 60% of cruise passengers (47,222) choose Antarctic programs, making Punta Arenas and Puerto Williams the main departure points for polar expeditions via the Drake Passage.

This specialization strengthens the region as a hub for international polar tourism, with infrastructure meeting International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO) standards.

Conservation and environmental challenges

Marine protected areas

Conservation of the strait’s unique ecosystem relies on several marine protected areas. The Francisco Coloane Marine Park is Chile’s first marine park, created to protect whales and their habitat.

The Los Pingüinos Natural Monument, established in 1982, protects Magdalena and Marta islands and their exceptional fauna. These measures aim to maintain ecological balance while allowing sustainable tourism.

Climate challenges

Climate change presents a major challenge for the strait’s ecosystem. Altered ocean currents, changing temperatures, and shifts in species distribution require constant scientific monitoring.

The Magallanes region is studied intensively to understand climate change’s impact on subantarctic biodiversity. This research informs broader understanding of environmental changes in polar regions.

A passage for the Future

The Strait of Magellan perfectly embodies the meeting of history and future, preservation and development. This legendary passage, discovered over five centuries ago, is regaining strategic importance in a world in energy and geopolitical transition.

A unique bi-oceanic corridor and sanctuary for exceptional biodiversity, the Strait of Magellan stands out as one of the planet’s most fascinating places. Its ability to unite economic development, environmental preservation, and tourist appeal could make it a model for polar regions in the 21st century.

For travelers seeking extraordinary discoveries, this maritime passage offers an unforgettable experience at Patagonia’s far south, with one continental shore and one insular. Between maritime history, extraordinary wildlife, and magnificent landscapes, this legendary passage continues to write the greatest chapters of human adventure at the world’s southern edge.

Bibliography – Magellan strait

Article published by Karukinka Association – August 4, 2025

Historical Sources and Exploration

- Revista de Marina (2025). The Incorporation of the Strait of Magellan. Maritime journal article. Available online: https://revistamarina.cl/articulo/la-incorporacion-del-estrecho-de-magallanes

- Wikipedia Contributors (2003-2025). Strait of Magellan. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strait_of_Magellan

- National Geographic España (2025). Ferdinand Magellan and the Insatiable Search for the Strait. National Geographic History. https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/fernando-magallanes-insaciable-busqueda-estrecho_7378

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1998-2025). Strait of Magellan: Location, Map, Importance, Climate & Facts. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Strait-of-Magellan

- Memoria Chilena (2000). European Navigators in the Strait of Magellan. National Library of Chile. https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-641.html

- Google Arts & Culture (2024). Strait of Magellan: The Water Frontier. Collaborative virtual exhibition. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/estrecho-de-magallanes-la-frontera-de-agua/OgVBx7rjDX9OLQ

Geography and Geology

- WorldAtlas (2021). Strait of Magellan. World Geographic Atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/straits/strait-of-magellan.html

- Wikipedia Contributors (2004-2025). Estrecho de Magallanes. Spanish Wikipedia. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estrecho_de_Magallanes

- Revista Mittofire (2019). The Strait of Magellan – Geological Origin (Part 1). Regional scientific publication. https://mittofire.com/origen-geologico-del-estrecho-de-magallanes-parte-1/

- iMariners (2023). Everything You Need to Know About the Strait of Magellan. Professional maritime guide. https://imariners.com/strait-of-magellan/

- DIRECTEMAR (2022). Overview of the Strait of Magellan. Chilean Maritime Authority. https://www.directemar.cl/directemar/generalidades-del-estrecho-de-magallanes

- Marine Insight (2024). 5 Strait of Magellan Facts You Must Know. Maritime knowledge platform. https://www.marineinsight.com/know-more/5-strait-of-magellan-facts-you-must-know/

Indigenous Peoples

- OEI Chile (2022). The Indigenous Peoples of the Strait of Magellan. Documentary video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q77jmvmaTCw

- Maritime Museum of Ushuaia (2008). Indigenous Peoples in Tierra del Fuego. Museum documentation. https://museomaritimo.com/en/indigenous

- Museo Precolombino (2021). Educational Notebook for Secondary Education – Indigenous Peoples of Magallanes. Educational manual (PDF). https://museo.precolombino.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/E.-Media-Magallanes.pdf

- Memoria Chilena (2011). Southern Chilean Peoples – Chonos, Kawéskar, Yámanas, Selk’nam, and Aónikenk. National archive. https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-3412.html

Kawésqar People

- French Wikipedia (2006-2025). Kawésqar. Online encyclopedia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kawésqar

- Spanish Wikipedia (2005-2025). Kawésqar. Online encyclopedia. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kawésqar

- Skorpios (2017). The Rituals of Kawésqar Culture. Cultural article. https://www.skorpios.cl/blog/pueblos-originarios/los-ritos-la-cultura-kawesqar/

- Marca Chile (2025). The 11 Indigenous Peoples of Chile. Informative article. https://www.marcachile.cl/los-10-principales-pueblos-indigenas-de-chile/

- Kawesqar.com (2020). The Kawésqar – Indigenous People Website. https://www.kawesqar.com/kawesqar-pueblos-originarios

Tehuelche-Aónikenk People

- Indigenous Peoples WordPress (2021). The Tehuelche People (including the Selknam). Ethnographic article. https://peuplesautochtones.wordpress.com/2021/08/20/chili-argentine-le-peuple-tehuelche-dont-les-selknams/

- Memoria Chilena (2000). Aónikenk. National archive. https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-93772.html

- Las Torres Blog (2023). Ancestral Patagonia: Following the Footsteps of Indigenous Peoples. Cultural tourism article. https://blog.lastorres.com/ancestral-patagonia-following-the-footsteps-of-the-indigenous-peoples

- Fundación Patricio Aylwin (2022). The Indigenous Peoples of the Far South. Academic study (PDF). http://fundacionaylwin.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/24.-Los-pueblos-indigenas-del-extremo-sur.pdf

- Casa Museo CAB Patagonia (2023). Historical Aboriginal Peoples of the Magallanes Region. Museum documentation. https://www.cab-patagonia.cl/casa-museo/los-aborigenes-historicos-de-la-region-de-magallanes

Selknam People

- French Wikipedia (2006-2025). Selknam. Online encyclopedia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selknam

- Rare Historical Photos (2023). Selknam Natives En Route to Europe for Exhibition in Human Zoos. Historical article. https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/selknam-natives-en-route-europe-exhibited-animals-human-zoos-1899/

- Radar Magazine (2022). Clash of Civilizations: The True History of the Selk’nam. Journalistic article. https://www.radarmagazine.net/clash-of-civilizations-selknam/

- Patagon Journal (2022). The Selk’nam’s Quest for Recognition in Chile. Specialized press article. https://www.patagonjournal.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4378%3Amarcio-pimenta-y-nina-radovic-fanta&catid=205%3Aindigenous-peoples&Itemid=340&lang=en

- Memoria Chilena (2023). Selknam Ritual, Shamanism, and Music. National cultural archive. https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-3687.html

- Ladera Sur (2017). A Look at the Selk’nam World through Body Painting. Cultural article. https://laderasur.com/articulo/una-mirada-al-mundo-selknam-desde-la-pintura-corporal/

Shamanism and Spirituality

- Academia.edu (2017). The Shamanism of the Fuegians. Academic article. https://www.academia.edu/33680567/6_El_Chamanismo_de_los_Fueguinos

- Nora Hansen (1944). The Yámana Shamans of Tierra del Fuego. Ethnological study (PDF). https://ddhh.bdigital.uncu.edu.ar/objetos_digitales/13605/pagesfromrev-anales-1944-tomov-2.pdf

- University of Granada (2008). Cosmology and Shamanism in Patagonia. University article. https://www.ugr.es/~pwlac/G19_09Beatriz_Carbonell.html

Colonial Context and Genocide

- The Conversation (2020). 500 Years After Ferdinand Magellan Landed in Patagonia, There’s Nothing to Celebrate for Its Indigenous Peoples. Academic article. https://theconversation.com/500-years-after-ferdinand-magellan-landed-in-patagonia-theres-nothing-to-celebrate-for-its-indigenous-peoples-132939

- Wikipedia (2022). Chilean Colonization of the Strait of Magellan. Online encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chilean_colonization_of_the_Strait_of_Magellan

- University of King’s College (2023). Early Modern Times – Dire Straits of Magellan. Academic article. https://ukings.ca/news/early-modern-times-dire-straits-of-magellan/

Fauna and Biodiversity

- Ladera Sur (2020). Pioneering Plants of the Strait of Magellan. Mountain and nature magazine. https://laderasur.com/fotografia/los-pioneros-vegetales-del-estrecho-de-magallanes/

- The Modern Postcard (2021). Magdalena Island and the Magnificent Magellanic Penguins. Punta Arenas travel guide. https://www.themodernpostcard.com/punta-arenas-chile-magdalena-island-the-magnificent-magellanic-penguins/

- AFAR Media (2022). Wildlife in the Strait of Magellan. Specialized travel guide. https://www.afar.com/places/strait-of-magellan-e7d95066-c6bf-4619-971d-650efbca0c6a

- Parque del Estrecho de Magallanes (2025). Flora and Fauna. Official park website. https://parquedelestrecho.cl/flora-y-fauna-2/

- Wikipedia Contributors (2004-2025). Magellanic Penguin. Wildlife encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magellanic_penguin

- El Español (2022). The Amazing Biodiversity of Magallanes (Chile) That Captivated Explorers. Enclave ODS. https://www.elespanol.com/enclave-ods/noticias/20220124/asombrosa-biodiversidad-magallanes-chile-cautivo-exploradores/644935772_0.html

- Swoop Patagonia (2015-2025). See Penguins in Chile & Argentina. Specialized Patagonia guide. https://www.swoop-patagonia.com/visit/wildlife/penguins

- Howlanders Travel (2025). Magdalena and Marta Island Navigation. Punta Arenas tour operator. https://www.howlanders.com/es/tours-chile/punta-arenas/navegacion-isla-magdalena

- Patagonia Chile Tourism (2020). Flora and Fauna. Official Patagonia tourism portal. https://patagonia-chile.com/experiencia/florayfauna/

- Aquarium of the Pacific (2024). Magellanic Penguins. Marine scientific documentation. https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/exhibits/penguin_habitat/magellanic_penguins

- Colegio Sofia Infante Hurtado (2021). Native Flora Manual of Magallanes. Regional educational guide (PDF). https://www.colegiosofiainfantehurtado.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Manual-Flora-Nativa-de-Magallanes.pdf

Navigation and Maritime Transport

- Mundo Marítimo (2025). Port of Punta Arenas and the Strait of Magellan Increase Their Importance for Global Maritime Transport. Specialized maritime publication. https://www.mundomaritimo.cl/noticias/puerto-de-punta-arenas-y-el-estrecho-de-magallanes-aumentan-su-importancia-para-el-transporte-maritimo-global

- Chilean Navy (Armada de Chile) (2025). Maritime Authority of Punta Arenas and the “Boka Vanguard” Passage through the Strait of Magellan. Official navy communiqué. https://www.armada.cl/noticias-navales/seguridad-e-intereses-del-territorio-maritimo/autoridad-maritima-de-punta-arenas-y-el-paso-del-boka-vanguard-por-el

- DIRECTEMAR (2025). Piloting in the Strait of Magellan. Official maritime regulations. https://www.directemar.cl/directemar/site/edic/base/port/estrechodemagallanes_es.html

- DIRECTEMAR (2020). Piloting Through the Strait of Magellan, Chilean Channels and Fjords. Official navigation manual. https://web.directemar.cl/pilotaje/paginaa.html

- GetBoat Blog (2025). Sailing the Strait of Magellan – Ultimate Boater’s Navigation Guide. Technical navigation guide. https://blog.getboat.com/travel-tips-advice/sailing-the-strait-of-magellan-navigation-guide/

- DIRECTEMAR (2008). Sailing Along the Strait of Magellan or the Drake Passage. Bilingual technical guide. https://web.directemar.cl/pilotaje/pageb.html

- DIRECTEMAR (2000). Piloting Through the Strait of Magellan, Chilean Channels and Fjords. Maritime piloting manual. https://web.directemar.cl/pilotaje/paginab.html

Climate and Meteorology

- Chilean Navy (Armada de Chile) (2020). Understanding Meteorology in the Strait of Magellan. Official meteorological study – 500 years of the Strait. https://www.armada.cl/estrecho-de-magallanes-500-anos/comprendiendo-la-meteorologia-en-el-estrecho-de-magallanes

- Sea Temperature Info (2025). Weather Forecast for the Strait of Magellan. Maritime meteorology service. https://seatemperature.info/es/estrecho-de-magallanes-prevision-del-tiempo.html

- Wikipedia Contributors (2009-2025). Williwaw. Encyclopedia of meteorological phenomena. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Williwaw

Tourism and Cruises

- Chile Excepcion (2025). Whale Watching in the Strait of Magellan, Patagonia. Specialized tour operator. https://www.chile-excepcion.com/circuits-chili/escapades-chili/baleines-detroit-magellan-patagonie

- InterPatagonia (2025). Magdalena and Santa Marta Islands. Punta Arenas travel guide. https://www.interpatagonia.com/puntaarenas/navigation-magdalena-santa-marta-islands.html

- ITV Patagonia (2025). Magallanes Closes 2024-2025 Cruise Season with 77,000 Passengers. Regional media – Tourist statistics. https://www.itvpatagonia.com/noticias/regional/25-04-2025/magallanes-cierra-temporada-de-cruceros-2024-2025-con-un-total-de-77-mil-pasajeros/

Economy and Development

- Chile Maritime League (2025). “The Strait of Magellan is a raw gem.” Professional maritime association. https://www.ligamar.cl/el-estrecho-de-magallanes-es-una-joya-en-bruto

- TRT Global Spanish (2024). Why the Strait of Magellan Is a Strategic Passage in Global Trade. International geopolitical analysis. https://trt.global/espanol/article/1493351100

- Revista de Marina (2025). Strait of Magellan and Green Hydrogen: Great Economic Potential. Official naval publication. https://revistamarina.cl/articulo/estrecho-de-magallanes-e-hidrogeno-verde-gran-potencial-economico

- SP Logistics (2025). Punta Arenas and the Strait of Magellan Gain Relevance in Global Maritime Transport. Specialized logistics analysis. https://web.splogistics.com/blog/post/1135/punta-arenas-y-estrecho-de-magallanes-ganan-relevancia-en-el-transporte-maritimo

- BioBío Chile (2025). The Strait of Magellan as Chile’s Major Bioceanic Corridor. Strategic opinion article. https://www.biobiochile.cl/noticias/opinion/columnas-bbcl/2025/06/05/estrecho-magallanes-corredor-bioceanico-estrategia-chile.shtml

- Memoria Chilena (2002). Punta Arenas and the Magellanic Economy (1848-1950). National historical archives. https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-784.html

![[#8 – Ireland–Scotland 2024] from Loch Buie to the sacred Isle of Iona](https://karukinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Iona_LL-1080x675.jpg)

![[#2 Ireland – Scotland 2024] From Dublin to Bangor (Belfast Lough)](https://karukinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Donaghadee_0420242-400x250.jpg)