Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve: an exceptional subantarctic sanctuary

Association Karukinka

Loi 1901 - d'intérêt général

Derniers articles

Suivez nous

The Cabo de Hornos Biosphere Reserve (Cape Horn Nature Reserve), established in 2005, is one of the southernmost and largest protected areas in the world, covering more than 4,884,000 hectares of southern lands and waters. It contains unique terrestrial and marine ecosystems, pristine subantarctic forests, remarkable biodiversity—including over 5% of the world’s bryophyte diversity—and the last populations of the Yaghan people, who maintain a millennia-old connection with these extreme landscapes.

Table des matières

The Cabo de Hornos Biosphere Reserve was included in UNESCO’s “Man and the Biosphere” program in June 2005, becoming both the southernmost and one of the largest biosphere reserves in South America. Spanning about 4,884,274 hectares, it comprises a terrestrial area of 1,917,238 ha and a marine area of 2,967,036 ha, integrating for the first time in Chile both marine and terrestrial ecosystems under a unified conservation status. The Alberto de Agostini and Cape Horn National Parks form the core protected area, where all infrastructure development is strictly prohibited.

1. Geography and zoning of the Cape Horn nature reserve

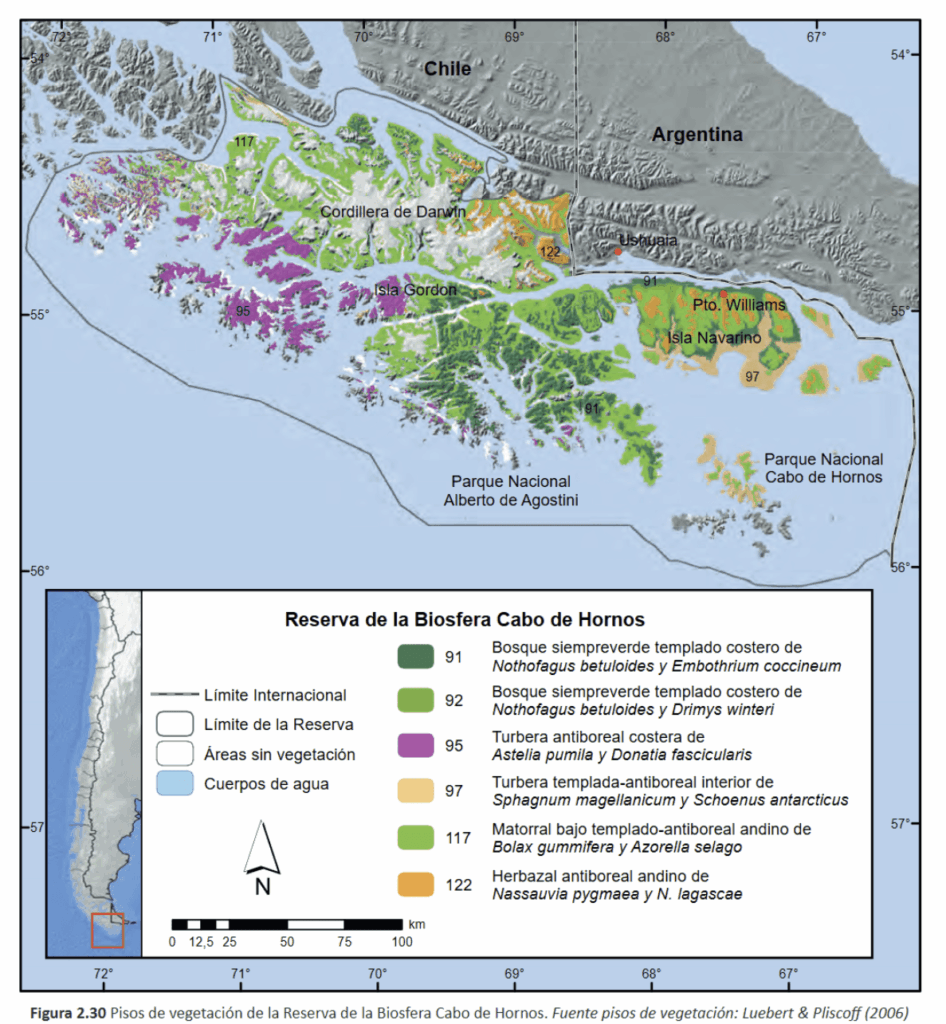

Geographically, the reserve extends across the Tierra del Fuego archipelago, between 54.1° S and 56.2° S latitude, and 66.1° W and 72.5° W longitude. It includes the Wollaston, Hermite, Navarino, and Hoste islands, as well as channels (including the Beagle Channel), fjords, and currents that form a landscape shaped by glaciations and tectonic activity. The UNESCO MAB Reserve zoning (Cabo de Hornos Biosphere Reserve, i.e., the southern Chilean marine reserve) is structured into three areas:

- The core zone (Alberto de Agostini National Park including the Darwin Range, and Cape Horn National Park) is strictly protected.

- The buffer zone, where light and sustainable activities are allowed.

- The transition zone, including isolated villages like Puerto Williams and limited infrastructure under a sustainable development framework.

2. Terrestrial and marine ecosystems

2.1 Subantarctic forest and peatlands

The reserve’s subantarctic forests are the southernmost on earth. Dominated by three Nothofagus species—N. pumilio, N. betuloides, and N. antarctica—they form both deciduous and evergreen stands, interspersed with peat bogs and alpine heaths. These forests are among the world’s rare examples of non-fragmented temperate forest. The organic-rich soils support vast carpets of bryophytes, typical of the cool, humid environment; these play a crucial role in the hydrological cycle and carbon sequestration.

2.2 Marine and coastal ecosystems

The marine component of the reserve centers around a complex network of fjords, channels, and underwater plateaus. The Humboldt current and the mixing of cold Pacific and Atlantic waters have fostered the development of kelp forests (Macrocystis pyrifera, Durvillaea antarctica) forming “underwater forests” that host diverse invertebrate fauna and fish communities. Intertidal habitats harbor macroalgae species and numerous endemic invertebrates, while the cold, oxygen-rich waters support populations of seals, sea lions, and several cetacean species.

3. Biological diversity and endemism: subantarctic biodiversity

3.1 Bryophytes and lichens

With over 300 species of liverworts and 450 species of mosses, the reserve is a global hotspot for bryophytes, representing more than 5% of global diversity on less than 0.01% of the world’s land surface. These communities, described as “miniature forests,” serve as sentinels for assessing the impacts of climate change and rising UV radiation.

3.2 Terrestrial and marine fauna

Terrestrial fauna include the southern river otter (Lontra provocax), the Magellanic woodpecker (Campephilus magellanicus), and other endemic birds. In the marine environment, the surrounding waters are home to black-browed albatross, giant petrels, Magellanic penguins, and stable populations of fur seals and leopard seals, highlighting the ecological importance of this protected area.

4. Biocultural dimension and Yaghan ethnology

The reserve is also a cultural sanctuary. The Yaghan, nomadic people of the southern channels, are the world’s southernmost indigenous group, with a presence dating back over 7,500 years, as evidenced by archaeological sites on Navarino Island. They continue to possess expert knowledge of canoe navigation and subantarctic ecology, and have actively participated in research within the reserve, particularly through the Omora Ethnobotanical Park near Puerto Williams. Their oral traditions, language, and knowledge of local flora and fauna are incorporated into educational and conservation programs. Ecotourism in Patagonia is also a key activity of the Omora initiative.

5. Governance and management

The reserve is managed by a board chaired by the regional governor, involving public agencies and local organizations. The scientific committee, coordinated by the Omora Park and the University of Magallanes, leads research, ecological monitoring, and participatory conservation efforts. In 2006, the reserve joined UNESCO’s Ibero-MAB network, strengthening transnational cooperation for research and training.

6. Threats and conservation challenges

Despite its isolation, the reserve faces several threats:

- Uncontrolled tourism development, particularly southern cruises and increased traffic around Cape Horn, poses risks of pollution and disturbance to marine wildlife.

- Intensive salmon farming in northern fjords introduces exotic species and degrades water quality. Salmon now breed in these waters, impacting native species such as the robalo.

- The spread of introduced species such as the North American beaver and mink threatens riparian forests, streamside habitats, and shorebird nesting sites.

Long-term monitoring programs, such as the Omora initiative and Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) stations, assess these pressures and propose adaptive measures. However, monitoring is hampered by the vastness of the reserve and its logistical challenges.

7. Research and education initiatives

7.1 Omora Ethnobotanical Park

Founded in 2000, the Omora Ethnobotanical Park is at the center of a transdisciplinary approach combining ecology, environmental philosophy, and “field philosophy” education. It offers educational trails, including “miniature forests,” to raise public awareness of bryophyte diversity and the link between biodiversity and Yaghan culture.

7.2 Cape Horn International Center (CHIC)

Inaugurated in 2020 in Puerto Williams, CHIC brings together researchers, artists, and indigenous communities to develop a model for biocultural conservation, technical training, and sustainable development. Its programs address the responses of biodiversity to climate change, the management of invasive species, and the formulation of public policy adapted to subantarctic zones.

The Cabo de Hornos Biosphere Reserve remains one of the rare refuges where harmonious coexistence between local inhabitants and ecosystems at the literal edge of the world is fully realized. Securing its future means strengthening participatory governance, managing invasive species, and supervising polar tourism under the banner of responsible ecotourism. Finally, the ongoing integration of Yaghan knowledge in research and education programs will ensure the preservation of both the biological and cultural heritage of this unique subantarctic sanctuary.

Bibliography

- Rozzi, R. et al. (2006). Ten Principles for Biocultural Conservation at the Southern Tip of the Americas: The Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve. Ecology and Society, 11(1). https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art43/

- Rozzi, R. et al. (2008). Multi-ethnic and Intercultural Education in the Biosphere Reserve at the Southern End of the Americas. In Price, M. F. (ed.), Biosphere Reserves of the World. UNESCO-MAB. https://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/

- Rozzi, R. et al. (2004). Omora Ethnobotanical Park: A Model for Integrating Biocultural Conservation and Environmental Philosophy in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve. Environmental Ethics, 26(2), 131–169. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics200426226

- Mittermeier, R. A. et al. (2003). Hotspots: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. Conservation International. https://www.conservation.org

- CONAF (Corporación Nacional Forestal). (2023). Reserva de la Biósfera Cabo de Hornos. Gobierno de Chile. https://www.chilebosque.cl

- Cape Horn International Center (CHIC). (2021). CHIC Strategic Plan 2021–2026. Universidad de Magallanes. https://www.centrochic.cl

- Anderson, C.B. et al. (2011). Exotic ecosystem engineers transform sub-Antarctic forest structure and function. Biological Invasions, 13, 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-010-9841-4

- Anderson, C.B. et al. (2019). Cape Horn’s Lessons for Sustainability. Science Advances (UNESCO CHIC/UMAG). https://advances.sciencemag.org/

- Unesco-MAB. (2005). Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve Dossier. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/

- Rozzi, R. et al. (2010). La Reserva de Biósfera Cabo de Hornos: una propuesta educativa y de desarrollo sustentable en el extremo austral de Chile. Universidad de Magallanes. Disponible sur la bibliothèque CHIC.

![[Sailing Patagonian channels] Sébastien’s Logbook part 1](https://karukinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Caleta-eva-luna_012025_Karukinka4-400x250.jpg)