The Beagle Channel (Onashaga): meeting place of oceans at the southernmost tip of the Americas

Association Karukinka

Loi 1901 - d'intérêt général

Derniers articles

Suivez nous

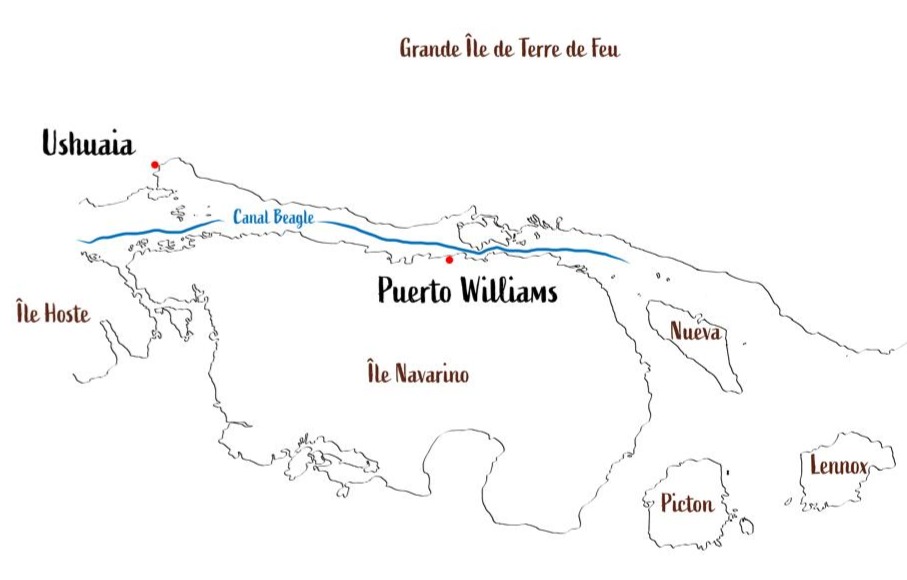

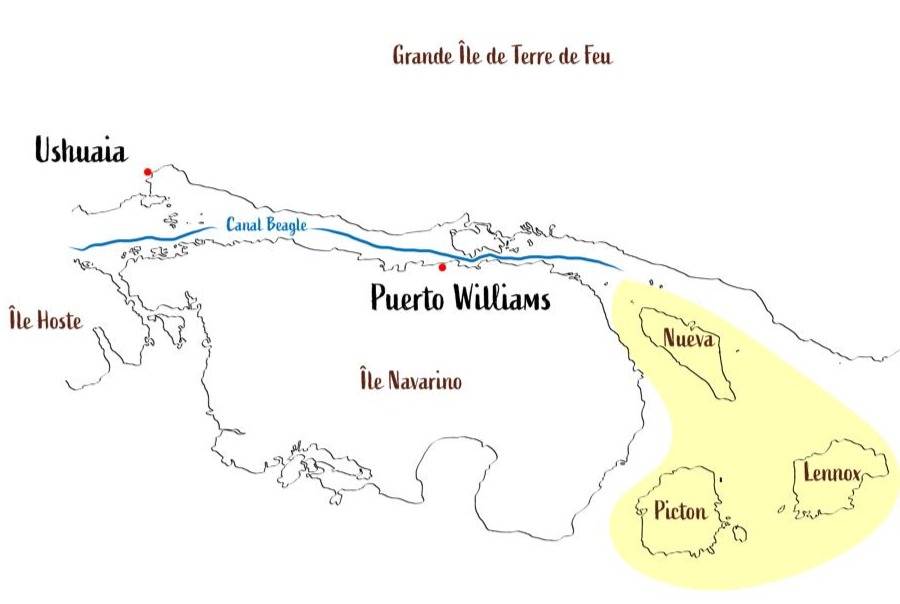

The Beagle Channel, known to the Yaghan people as Onashaga (“channel of the Ona hunters,” i.e., their Selk’nam neighbors from Tierra del Fuego), is one of the planet’s outstanding maritime passages. This interoceanic strait, approximately 270 kilometers long, connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans at the very southern tip of South America, separating the main island of Tierra del Fuego from an archipelago of smaller islands between 54°50′ and 55°00′ south latitude.

For us, who regularly sail these legendary waters, Onashaga—the Beagle Channel—means much more than a simple maritime passage: it’s a world of its own, where two oceans meet and where seven millennia of Yagan navigation still resonate.

Table des matières

The genesis of the landscape: a glacial heritage

When ice sculpted the channels

The formation of the Beagle Channel is a prime example of Quaternary glacial sculpting, which has shaped one of the most spectacular southern hemisphere landscapes. During repeated Pleistocene glaciations, glaciers hundreds of meters thick excavated valleys like Carbajal and Lake Kami (Fagnano), creating the region’s complex topography.

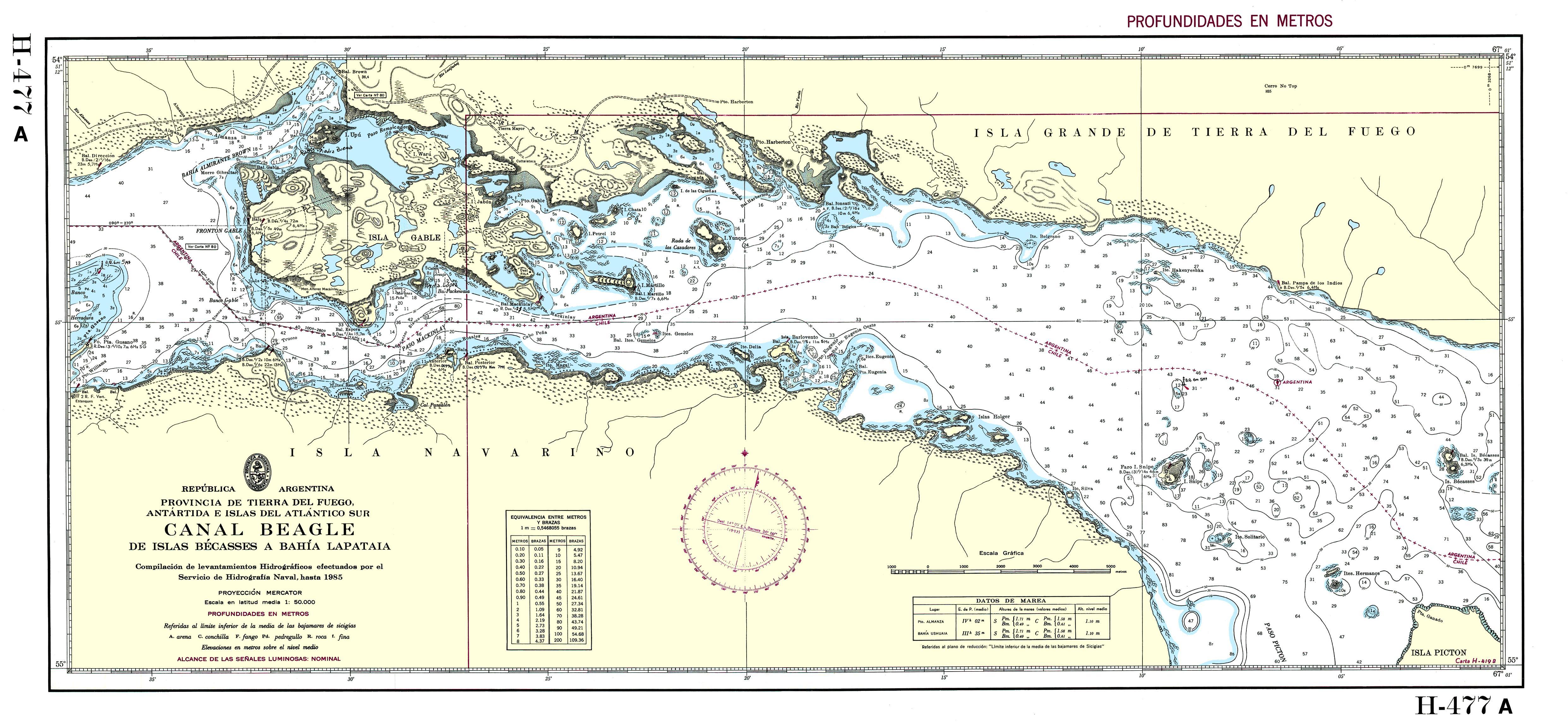

The glacier responsible for forming the Beagle Canal moved from west to east, fed by the Darwin Range, where glaciers and snowfields—remnants of this genesis—can still be seen today. This glacial process left behind moraine deposits in the shallower areas, especially around Gable Island and off the Ushuaia Bay, creating today’s bathymetric complexities.

The tectonic structure underlying the channel is a longitudinal tectonic valley, later modified by glacial action. The combination of tectonic and glacial processes resulted in a morphology with semi-isolated basins as deep as 400 meters, separated by shallow topographic sills that control water mass circulation.

A complex submarine architecture

The Beagle Channel’s bathymetry reveals a complex architecture dominated by a series of shallow sills, dividing the channel into several distinct micro-environments. In the western sector, the Diablo Island sill (approx. 50 meters deep) and the Fleuriais Bay sill (about 100 meters) separate the northwestern and southwestern branches from the central sector.

This bathymetric setup generates a complex circulation system, with sills acting as barriers that limit the exchange of deep water masses, creating micro-environments with distinctive physical, chemical, and biological properties.

It is this diversity of habitats that makes the Beagle Channel such a rich and unique ecosystem, as explained by Centro IDEAL researchers who have studied these waters for years.

Hydrographic system

The meeting of oceans

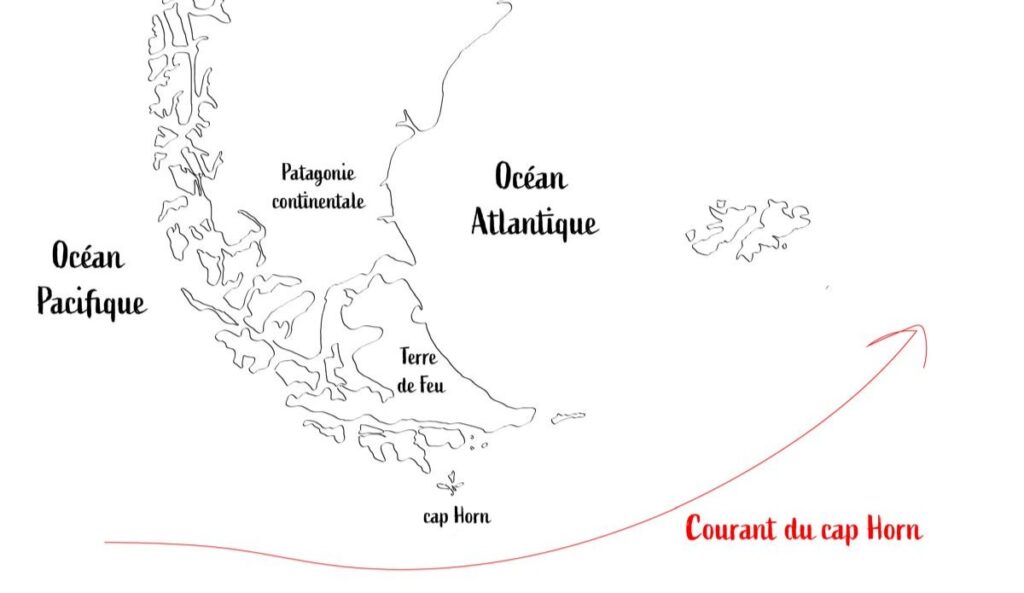

The Beagle Canal acts as an interoceanic corridor that facilitates the transport of surface waters from the Pacific to the Atlantic, a flow mainly driven by the difference in sea level between the two oceans and the influence of strong westerly winds within the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

The Cape Horn current is the primary source of water entering the channel, bringing subantarctic water (SAAW) at depths greater than 100 meters along the edge of the Patagonian Pacific shelf. This water enters via a submarine canyon at the western mouth of the channel, characterized by temperatures of 8–9°C, salinity above 33, and relatively low oxygen concentrations.

Waters that tell the story of the climate

Freshwater input from the Darwin Cordillera icefield generates a two-layer system, with a pronounced pycnocline separating vertical phytoplankton fluorescence. This estuarine water is cold (4–6°C), nutrient-poor, and highly oxygenated.

Time series analyses reveal that the annual cycle explains 75–89% of ocean temperature variability, while the atmospheric cycle explains 53% of its variability.

These data allow us to understand how the channel reacts to climate change, emphasize oceanographers monitoring these waters.

A sanctuary for marine biodiversity

The realm of marine mammals

The channel hosts an exceptional diversity of marine mammals, internationally recognized as an important marine mammal area (IMMA), covering 26,572 km² from the channel to Cape Horn. This area is home to at least eleven primary marine mammal species, plus eight supporting species.

Among the year-round resident species are three small cetaceans: the Peale’s dolphin (Lagenorhynchus australis), the dusky dolphin (L. obscurus), and the Burmeister’s porpoise (Phocoena spinipinnis), along with two pinnipeds: the South American sea lion (Otaria byronia) and the South American fur seal (Arctocephalus australis).

We have had the chance to observe these Peale’s dolphins during our voyages across Patagonia’s channels, from the channel’s eastern mouth to Cook Bay at its southwestern end. Their close association with kelp forests is fascinating: they undertake 40.5% of their feeding and 14.3% of their hunting behaviors there.

The underwater kelp forests

The underwater forests of Macrocystis pyrifera, locally known as “cachiyuyos,” are among the channel’s most important ecosystems, extending from the Valdés Peninsula to Tierra del Fuego. These forests provide a critical habitat, acting as nursery grounds, refuges, and feeding areas for an exceptionally diverse range of marine species.

Doctoral research by Adriana Milena Cruz Jiménez revealed the complexity of fish assemblages associated with these forests, examining various strata: the lower area at the holdfast and the mid-water area at the fronds.

The ichthyological diversity found in these kelp forests highlights their vital role in marine biodiversity, explains this specialist.

A delicate balance under threat

The pattern of nutrient distribution in the Beagle Channel varies distinctly among its water masses. The system is notably nitrate-limited, with an N:P ratio of 8.42, consistent across all water masses. This directly influences the channel’s primary productivity.

Phytoplankton biomass is generally moderate and limited to the upper pycnocline in the western sector, while mixing over sills disrupts stratification, pushing phytoplankton cells beneath the photic zone, which can limit primary production.

Local scientists insist that understanding these mechanisms is crucial to preserving the unique balance of this ecosystem.

The Yagan cultural heritage: the Onashaga (Beagle) Channel

Seven millennia of navigation

The name Onashaga means “channel of the Ona hunters” in the Yagan language and reflects the profound connection between this maritime people and these waters for around 7,000 years. The Yagan developed a nomadic culture based entirely on exploiting marine resources and constant navigation of the Fuegian archipelago, adapting to an environment Europeans found utterly inhospitable.

When we sail these waters, we still feel the presence of those ancient navigators, as our crew members testify. Their traditional territory extended from the southern coast of the main Tierra del Fuego island (Onaisin) to the Cape Horn archipelago, including the Onashaga. This toponym is one of the many native place names erased from official maps by colonization, which we must now reclaim to restore meaning rooted in the land’s first inhabitants.

The channel as an archaeological witness

Archaeological evidence along the Beagle Channel reveals human occupation stretching back millennia, with shell middens, lithic tool workshops, fish traps, and ancient campsites.

Notable archaeological sites include evidence of ancient Yagan settlement at places like Wulaia Bay on Navarino Island, indicating occupation over 7,000 years ago.

The legacy of great explorations

In the footsteps of Darwin and FitzRoy

The channel is named after HMS Beagle, the British ship that conducted the first hydrographic survey of southern South America’s coasts from 1826 to 1830. The European discovery of the channel occurred in April 1830, when the Beagle was anchored in Orange Bay (southeast Hoste Island).

During the second expedition (1831–1836), FitzRoy brought along Charles Darwin as a self-financed naturalist. Darwin saw his first glaciers there in January 1833, writing in his journal: “It is almost impossible to imagine anything more beautiful than the beryl-blue of these glaciers, especially contrasted with the dead white of the upper snow stretches.”

Darwin’s meticulous observations of the region’s geology, fauna, and indigenous populations provided key evidence for his understanding of adaptation and geographic species distribution.

The channel thus became one of the seminal natural laboratories in the history of natural sciences.

From mapping to geopolitical conflict

The hydrographic surveys by Captain FitzRoy and crew laid the groundwork for modern navigation in the region, followed by those from the Cape Horn Scientific Mission. However, this mapping precision also revealed the strategic importance of the channel, which would become a historic source of geopolitical tensions between Chile and Argentina.

The Beagle conflict of 1978 brought the nations to the brink of war over three small islands—Picton, Lennox, and Nueva—whose sovereignty would determine control over vast maritime territories. The dispute was resolved by papal mediation, with Pope John Paul II playing a crucial role, leading to the treaty of peace and friendship of 1984.

Modern science in the service of knowledge

A monitored natural laboratory

Today, the channel is one of the best-studied subantarctic marine systems, serving as a comprehensive regional sentinel of global change. Since October 2016, Chile’s Austral University’s Centro IDEAL has conducted annual hydrographic transects from the western end to Yendegaia Bay.

A major milestone was achieved in July–August 2017 with the first complete, high-resolution oceanographic survey along the entire channel, carried out through cooperation between Centro IDEAL and an Argentine expedition on the research vessel Bernardo Houssay. This international collaboration generated, for the first time, a complete hydrographic section of the channel, say the researchers involved.

Unique scientific challenges

Research in the Beagle Channel faces unique challenges due to its remote location, complex geomorphology, and shared jurisdiction between Chile and Argentina, historically limiting coordinated research. Future needs include studies on processes within each semi-enclosed basin and implementation of coupled atmosphere-ocean-glacier models to determine residence times.

Such research is crucial to understanding how this ecosystem will respond to future climate change.

Threats and conservation issues

The challenges of climate change

This channel faces unprecedented threats from climate change: rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and ocean acidification, all threatening the ecosystem’s delicate balance. Glacier retreat has accelerated dramatically in recent decades, altering freshwater contributions and potentially affecting marine productivity.

Changes have already been observed during our expeditions: the retreat of glaciers between 2018 and 2025 left a lasting impression. Scientists closely monitor these changes, using the region as a natural laboratory to understand wider impacts of climate change.

The salmon farming controversy

The expansion of the salmon farming industry into the region has been categorically rejected by organizations grouped within the Forum for the Conservation of the Patagonian Sea, which express concern over potentially catastrophic and irreversible damage to one of the region’s most precious marine ecosystems.

We strongly support this position: the channel’s pristine waters are home to one of the world’s greatest biodiversity reserves, with great heterogeneity in coastal-marine habitats containing numerous understudied marine invertebrates and vertebrates. Introduction of non-native species such as salmon is considered “terrible and risky” for this ecosystem by leading researchers. Fish-farm salmon escapes upstream have led to “wild salmon” appearing in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, now threatening endemic species such as robalo.

A challenge of international and multicultural preservation and cooperation

Since 2005, in order to preserve this natural marvel, most islands south of the Beagle are part of the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, managed by UNESCO, CONAF, and the Chilean Navy. This designation acknowledges the ecosystem’s outstanding importance and establishes long-term conservation frameworks.

We believe that preserving Yagan culture and integrating their ancestral knowledge is essential to understanding and protecting this unique ecosystem. Including Yagan traditional ecological knowledge in contemporary environmental management represents an opportunity to develop innovative approaches to conservation. Knowledge of navigation, climate observation, marine resources, and seasonal cycles forms a scientific heritage of great value, complementing modern research methodologies.

Bibliography

Scientific sources

Ferreyra, G. & González, H. “General hydrography of the Beagle Channel, a subantarctic interoceanic passage at the southern tip of South America.” Frontiers in Marine Science, September 30, 2021.

Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force. “Beagle Channel to Cape Horn IMMA – Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force.” Marine Mammal Habitat, March 18, 2024.

Lodolo, E., Menichetti, M. & Tassone, A. “Shallow architecture of Fuegian Andes lineaments based on marine geophysical data.” Andean Geology, vol. 45, no. 1, 2018.

Institutional publications

Yaghan’s, explorers and settlers. Museo Yaganusi, Government of Chile. PDF document, 2021.

Canal Beagle sin salmoneras. Mar Patagónico, regional declaration, 2024.

The Beagle Channel free from salmon farming. Mar Patagónico, regional statement, 2024.

Phytoplankton biodiversity and water quality in the Beagle Channel, Argentina, 2017–2021. Government of Argentina, PDF document.

Articles

El Rompehielos. “The importance of marine biodiversity in the Beagle Channel.” January 29, 2020.

Radio del Mar. “Beagle Channel is a key research ecosystem for marine biology.” May 22, 2023.

Centro IDEAL. “Scientists unravel the structure of the Beagle Channel.” November 11, 2021.

Audiovisual docs

“Discovery of the Beagle Channel.” YouTube, June 20, 2021.

“The importance of marine biodiversity in the Beagle Channel.” YouTube, January 29, 2020.

Conservation organizations

Rewilding Chile. “Beagle Channel: exploring the end of the world.” September 3, 2023.

Rewilding Chile. “Canal Beagle: explorando el confín del mundo.” September 3, 2023.

![[Sailing Patagonian channels] Sébastien’s Logbook part 1](https://karukinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Caleta-eva-luna_012025_Karukinka4-400x250.jpg)