Where is Cape Horn? Location and the Characteristics of a Mythic Geographic Landmark

Association Karukinka

Loi 1901 - d'intérêt général

Derniers articles

Suivez nous

Cape Horn (Cabo de Hornos in Spanish, Kaap Hoorn in Dutch, Loköshpi in the Yaghan language) is far more than just a geographic point. Located at 55°58′ south latitude and 67°16′ west longitude, this rocky promontory at 425 meters above sea level marks the southernmost point of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago and symbolically marks the meeting of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. At 965 kilometers from the Antarctic continent and just 138 kilometers from Ushuaia, Cape Horn rises as the ultimate sentinel of the Americas before the vastness of the Southern Ocean.

Table des matières

Geographical Position of Cape Horn

Location within the Fuegian archipelago

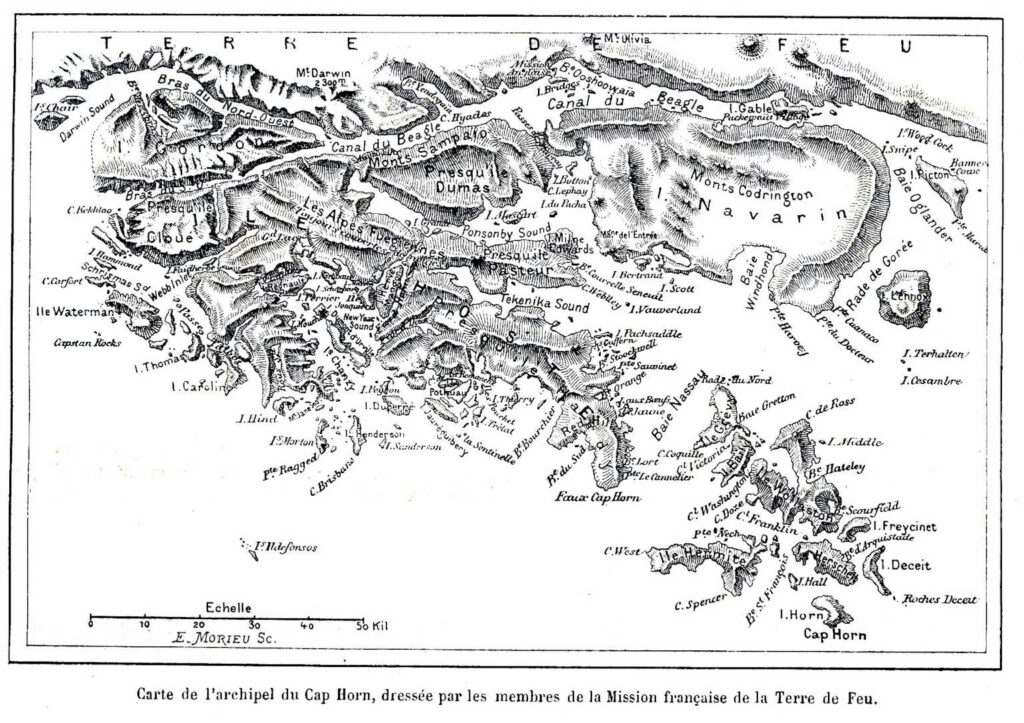

Cape Horn is situated on Horn Island (Isla Hornos), the southernmost island of the Hermite archipelago, itself part of the vast island complex of Tierra del Fuego. This modestly sized island (approximately 6 km by 2 km) is administratively part of the commune of Cabo de Hornos, in the Antarctic Province, within the Magallanes and Chilean Antarctic Region.

Contrary to popular belief, Cape Horn is not the southernmost point of the South American continent — that title belongs to the Diego Ramírez Islands, located 105 kilometers to the west-southwest. However, Cape Horn remains the southernmost of the great historical sailing capes and the most symbolic nautical waypoint in the Southern Hemisphere.

Precise Coordinates and Strategic Distances

With exact coordinates of 55°58′28″ south latitude and 67°16′10″ west longitude, Cape Horn lies at a unique geographical intersection where the major oceans of the Southern Hemisphere converge:

- Distance from Ushuaia (Argentina): 138 km to the north-northwest

- Distance from Puerto Williams (Chile): 56 km to the north

- Distance from the Antarctic continent: 965 km to the south

- Distance from the geographic South Pole: 2,535 km

Geological Formation and Geomorphology

Regional geological context

The Cape Horn region is embedded in the complex geological history of Tierra del Fuego, shaped by Andean orogeny and Quaternary glaciations. The archipelago was formed through a process of collapse and fragmentation of the southern tip of the Andes, amplified by glacial erosion and rising sea levels following the last Ice Age.

The geological formations of Horn Island consist mainly of sedimentary and volcanic strata from the Upper Cretaceous period, bearing witness to the intense tectonic activity related to the closure of the Rocas Verdes marginal basin and the early stages of Andean compression. This explains the rugged topography of the region, characterized by moderate elevations but extremely fragmented coastlines.

Coastal Morphology

To sailors, Cape Horn appears as a 425-meter cliff dropping directly into the ocean. This distinctive coastal morphology is the result of marine erosion, Quaternary glacial-interglacial cycles, and ongoing tectonic activity.

The Magellan-Fagnano Fault, a left-lateral strike-slip fault running east–west through Tierra del Fuego, indirectly influences the geomorphology of the Cape Horn region. With a movement rate of approximately 6.4 mm/year, this fault is a reminder of the continuous tectonic activity that shapes this part of the world.

- Preparing for Kreeh Chinen Festival

The crew of Milagro will be present, as a partner,… Read more: Preparing for Kreeh Chinen Festival

The crew of Milagro will be present, as a partner,… Read more: Preparing for Kreeh Chinen Festival - A Yagan story: the hummingbird (Omora or Sámakéar)

Today we share with you a Yagan story dedicated to… Read more: A Yagan story: the hummingbird (Omora or Sámakéar)

Today we share with you a Yagan story dedicated to… Read more: A Yagan story: the hummingbird (Omora or Sámakéar) - The dialogue between a Machi and ecologists opens new routes to integrate Mapuche knowledge in nature conservation

The study proposes a collaboration model between ancestral Mapuche knowledge… Read more: The dialogue between a Machi and ecologists opens new routes to integrate Mapuche knowledge in nature conservation

The study proposes a collaboration model between ancestral Mapuche knowledge… Read more: The dialogue between a Machi and ecologists opens new routes to integrate Mapuche knowledge in nature conservation

Oceanographic and Climatic Environment

The Drake Passage and Its Features

Cape Horn marks the northern boundary of the Drake Passage, an 809-kilometer-wide strait separating South America from the Antarctic Peninsula. This strait represents the shortest distance between Antarctica and any other continental landmass, only 135 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, between Cape Horn and Snow Island in the South Shetlands.

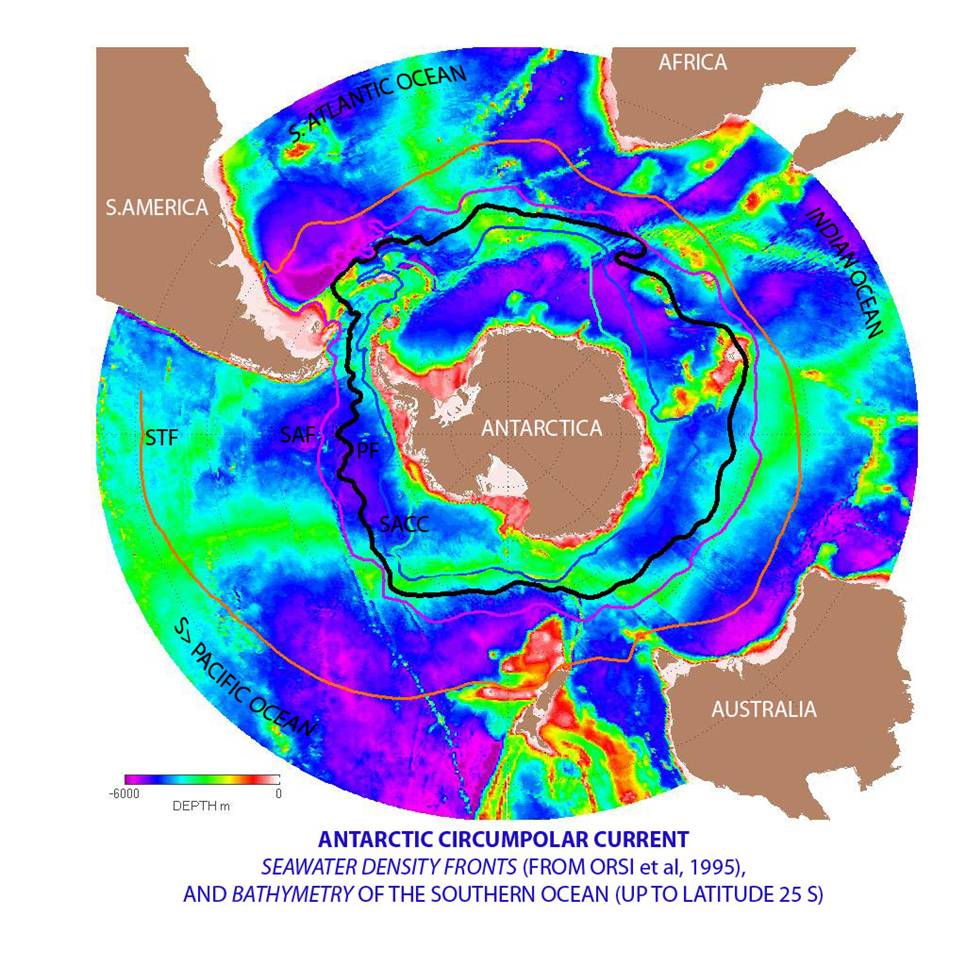

Antarctic Circumpolar Current

The Drake Passage is the point of maximum constriction of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) — the most powerful ocean current on Earth. The ACC transports an average of 150 million cubic meters of water per second — nearly 100 times the combined flow of all the world’s rivers. Its strength peaks at Cape Horn.

This oceanographic phenomenon is the main driver of the extreme weather conditions in the region. With no continental barriers, the ACC fuels the relentless west winds known as the “Roaring Forties” and “Furious Fifties”.

Subpolar Oceanic Climate

Cape Horn enjoys a subpolar oceanic climate, with relatively stable yet cold year-round temperatures. Average temperatures hover around 5°C, and the area receives up to 2,000 mm of rainfall annually, with nearly 278 days of rain per year.

Wind is the dominant climatic factor, averaging 30 km/h but frequently exceeding 100 km/h during storms. These conditions are directly linked to Cape Horn’s position within the zone of the Furious Fifties — a corridor of uninterrupted westerly winds that circle the Southern Hemisphere.

Biodiversity and Conservation Status

Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO)

Since 2005, Cape Horn has been part of the Cabo de Hornos Biosphere Reserve, recognized by UNESCO under the Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB). The reserve spans 4,884,273 hectares, encompassing a core area of 1,347,417 hectares composed of the Alberto de Agostini National Park and Cape Horn National Park.

Cabo de Hornos National Park

The Cabo de Hornos National Park, created on April 26, 1945, spans 63,093 hectares and includes the Wollaston and Hermite archipelagos. It is the southernmost protected area on the planet, hosting unique subantarctic ecosystems adapted to harsh climatic conditions.

Exceptional Biodiversity

The Cape Horn region is home to the southernmost forest ecosystem in the world and harbors 5% of the planet’s bryophyte species (mosses and liverworts).

The flora comprises Magellanic subpolar forests, dominated by Nothofagus species (southern beeches), alongside rich communities of mosses, lichens, and ferns adapted to extreme cold and humidity.

The marine fauna is equally impressive: humpback whales, southern dolphins, South American sea lions, elephant seals, and orcas are frequently observed. The birdlife is dominated by black-browed albatrosses, giant petrels, Magellanic penguins, imperial cormorants, and even Andean condors.

Maritime History and European Discovery

The Discovery of 1616

Cape Horn was discovered on January 29, 1616, during a Dutch expedition led by Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire. They sought an alternative to the Strait of Magellan to bypass the trade monopoly of the Dutch East India Company.

The cape was named in honor of the Dutch town of Hoorn, the expedition’s port of origin. This discovery profoundly altered maritime trade routes by offering a new corridor — broader than the Strait of Magellan, but vastly more dangerous.

A Historic Trade Route

For nearly three centuries, Cape Horn was a crucial maritime passage for global trade routes. Large sailing ships — known as “Cape Horners” — traversed these waters carrying goods between Europe, the Americas, and Asia: including nitrate, grain, wool, and gold from Australia.

The era of the great sailing ships ended with the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. The last commercial sailing vessel to round the Horn was the Pamir, in 1949, marking the close of a legendary chapter in maritime history.

Indigenous Context and Cultural Memory

The First Inhabitants

Before European colonization (1860–1920), the Cape Horn region was solely inhabited by the Yaghan people (also Yámana) — marine nomads who navigated these waterways in bark canoes. These hunter-gatherers developed an extraordinary maritime culture adapted to the severe subantarctic climate.

The Cape Horn promontory was called Loköshpi in the Yaghan language, reflecting a rich indigenous toponymy. According to research by Karukinka Association, over 3,000 indigenous place names (in Yaghan, Haush, and Selk’nam) have been recorded in the area, revealing a detailed and sensitive knowledge of the landscape.

Preservation and Memory Work

For over a decade, the Karukinka Association, founded by Lauriane Lemasson in 2014, has worked to archive, preserve, and honor the memory of the indigenous cultures of the Cape Horn region. Their expeditions in the Patagonian channels, from Tierra del Fuego to Cape Horn, have contributed to sound archives, toponymic mapping, and cultural education.

This work is all the more crucial when one considers that these peoples experienced cultural genocide in the early 20th century, their population declining from over 10,000 individuals to fewer than 500 by 1920.

Contemporary Challenges and Futures

Tourism and Conservation

Cape Horn now attracts a growing number of expedition cruises, mostly departing from Ushuaia or Punta Arenas. While weather constraints limit visitor numbers, increased traffic poses conservation challenges for fragile ecosystems.

Chile maintains a military base on Horn Island, with a garrison, a chapel, and a lighthouse. The lighthouse keeper and their family constitute the only permanent inhabitants of this isolated place.

Scientific Research

Cape Horn continues to be a site of important scientific research, particularly regarding climate change, oceanography, and subantarctic biodiversity. The work of the Karukinka Association and its partners contributes to the growing body of knowledge on extreme ecosystems undergoing rapid transformation.

Conclusion

Cape Horn occupies a unique place on the globe — both physically and symbolically. Situated at the southern tip of Horn Island in the Hermite archipelago, at 55°58′ South and 67°16′ West, it marks the symbolic point of convergence between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, between the Americas and Antarctica.

Its geographic position explains its extreme oceanographic and climatic conditions, forged over millennia of tectonic, glacial, and atmospheric dynamics. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the furious westerly winds, and the legendary nature of the Drake Passage make this one of the most dangerous maritime zones in the world.

Yet beyond the physical landscape lies a story of human history, resilience, tragedy, and conservation — from the Yaghan navigators to the Dutch explorers, from the age of sail to the fight to protect its fragile ecosystems.

To understand Cape Horn is to grasp the essence of a place where extremity meets universality, and where the end of the world becomes a mirror of the planet’s past, present, and future.

![[Sailing Patagonian channels] Sébastien’s Logbook part 1](https://karukinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Caleta-eva-luna_012025_Karukinka4-400x250.jpg)