Waves, winds, animals… In Patagonia, Lauriane Lemasson collects the sounds of a forgotten world (Géo Aventure, by Sébastien Desurmont, March 6, 2020)

Association Karukinka

Loi 1901 - d'intérêt général

Derniers articles

Suivez nous

Ethno-acoustician Lauriane Lemasson is passionate about the relationships that peoples weave with their sonic environment. Her profession drives her, microphone in hand, to brave the harsh expanses of Patagonia. Her goal: to better understand the settlement dynamics and cultural sources of inspiration of the Indigenous peoples who once inhabited these remote regions before being decimated.

Source: https://www.geo.fr/aventure/vagues-vents-animaux-en-patagonie-elle-collecte-les-sons-dun-monde-oublie-198494 (translated from French by Karukinka)

A land of silence and infinite spaces. In this Argentine Patagonian pampa, stretching out as if it would never end, people are few and not very talkative. There is no point in asking for directions. Apart from a few shaggy sheep who themselves seem to wonder what they’re doing there, there is no one left to answer in these places.

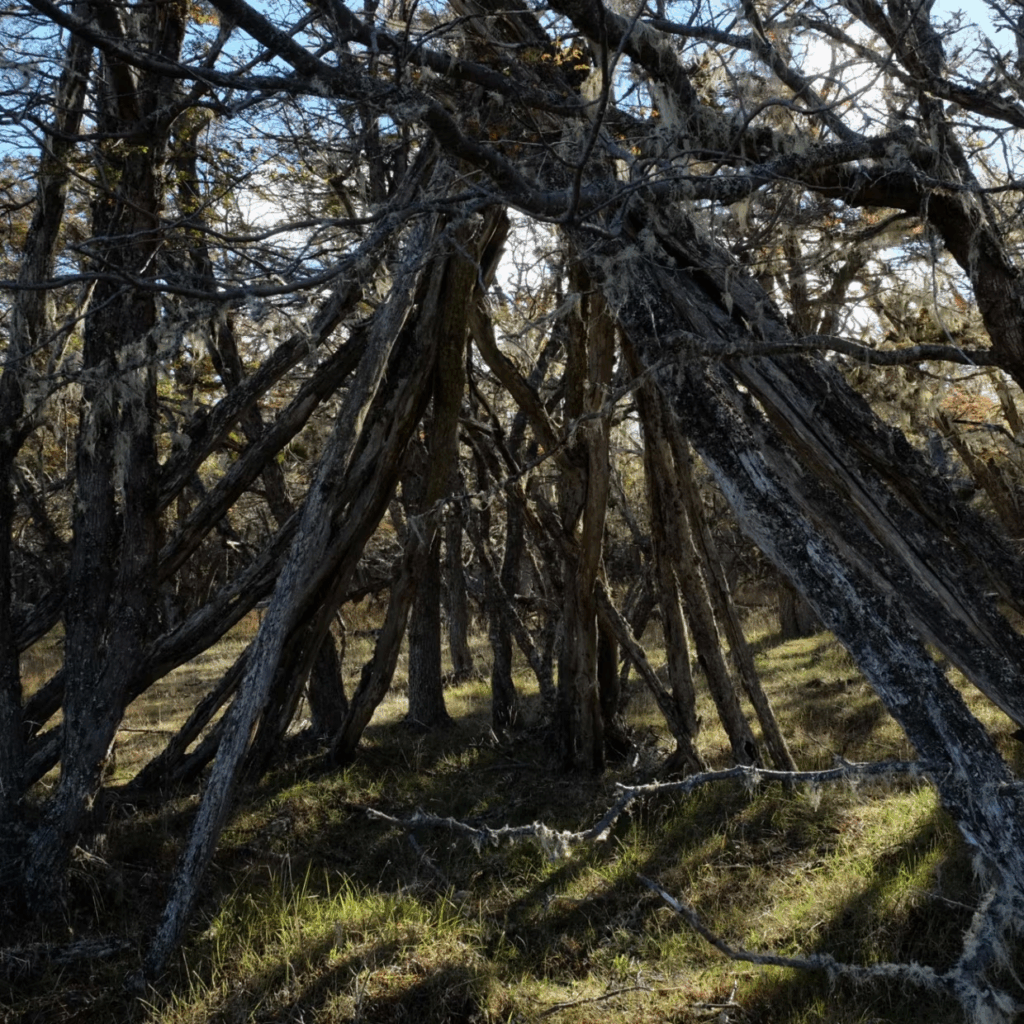

In any case, south of 53° South, once past the bustling Strait of Magellan (or Magellan Strait), there is hardly more than a single real road on this gigantic archipelago that is Tierra del Fuego: Ruta No. 3, a licorice-colored ribbon winding from north to south, linking the town of Rio Grande to the port of Ushuaia. Otherwise, this antipode—one of the least populated in the southern cone of South America—consists of vast steppes speckled with dark lakes, unassailable mountains, and forests thrown to the margins of the ocean.

All on Foot

And to make matters worse, everywhere there are gnarled, half-bent shrubs twisted by the gusts, impenetrable thickets, lines of rusty barbed wire, and endless fences that seem to conspire to block access to the vast private estancias that still checker most of this land. That’s the setting: a void as staggering as it is hostile. And no welcoming committee.

Yet it is in this complicated land that Lauriane Lemasson, 30 years old, has chosen to lose herself, alone, for months on end, traveling only on foot and always off the main marked road. This strong-willed young Breton woman has stepped over obstacles and ignored prohibitions in order to go “where no one goes anymore,” except for the gauchos. In short, a true wandering adventure. And in complete autonomy, burdened with a 25-kilo backpack in which Lauriane packed her gasoline stove, enough provisions to last between seven and nineteen days without resupply depending on the journey, her tent, her sleeping bag, her trusty Leica camera, her notebooks, and above all a host of microphones and recording equipment.

A Compass and a Map

She often forgot to look for shelter for the night—“in any case, most of the time there wasn’t any,” she recalls—and on her first escape, our tireless walker didn’t even have a GPS, just a compass and a good old 1:750,000 scale map. The goal of these rough outings? “To capture the sounds of the Patagonian landscapes,” she answers quite seriously. A strange quest, an unusual plan.

Because here, apart from the gusts that sometimes whistle so loudly they can make you deaf, silence and contemplation reign. “Very quickly, you realize that this space is inhabited by a thousand little sounds that truly sketch out the soundscapes I’m chasing,” Lauriane admits. The timid cries of birds, the plaintive creaking of trees in the storm, the grunting of sea lions, the distant cracking of glaciers… The slightest echo becomes, for our explorer, a kind of company.

The Violence of the Elements

“During my first journey across Tierra del Fuego,” she recalls, “over three and a half months of wandering, I met, outside urban areas, only three people: two estancieros, ranch workers who couldn’t believe they were seeing a Frenchwoman walking alone in the area, and an old Argentinian, a retiree who became my friend. He has since passed away, but he lived in isolation and welcomed me into his home without hesitation one day when the weather was very bad…”

Rain, snow, storms, blazing sun, sweltering heat, or chills rising from Antarctica… This region has always faced the violence and magic of the elements. Before it was discovered by the West during Magellan’s expedition in 1512, medieval portolan charts summed up the area with a few uncertain notes: “fogs,” “end of the world,” “anti-land.” But it takes more than that to throw off our adventurer. Because Lauriane is not just an explorer. And she’s certainly not a female Don Quixote chasing impossible windmills.

A Thesis in Ethnomusicology and Acoustics

A doctoral student at the Sorbonne, she conducts her sonic explorations as part of a rigorous, multidisciplinary thesis in ethnomusicology and acoustics. This unprecedented research project, which she began in 2011, is based on an initial intuition that she continues to test during her expeditions in Tierra del Fuego: “My explorations between Rio Grande and Ushuaia, in the Corazón de la Isla provincial reserve near Lake Fagnano, on the Beagle Channel, and through the Cape Horn biosphere reserve are all founded on a conviction. The sounds of these places (soundscapes) can still teach us things about the Amerindian peoples who once inhabited them—provided we listen carefully to what they have to say,” she explains. Just as every corner of the planet has its particular smell, colors, and temperatures, an ambiance is also shaped by its acoustics.

“Everyone has experienced this,” the scientist points out. “Whether you are in front of a mountain, in a forest, in a desert, or at the center of an ancient theater, the soundscape influences how we occupy and perceive a place. This is what I try to understand, adding the filters of history, geography, and anthropology.”

From this perspective, analyzing the acoustic dimension of an archaeological site, an ancient Amerindian camp, or a sanctuary where shamanic rituals once took place makes it possible to better explain the past, or even to reconstruct part of the environment and culture of those who lived there.

Microphone in Hand, Ears on Alert

The researcher has traveled more than 2,000 kilometers on foot, driven by a single goal: to once again hear the echoes of the first Fuegian peoples, these Patagonian natives who are now virtually unknown to the general public. “Most books and articles on the subject claim that these Amerindians, who arrived in Tierra del Fuego more than 10,000 years ago, disappeared long ago,” Lauriane protests. “But from my very first trip, I realized the reality was quite different: descendants of these Indigenous peoples—exterminated by European colonists or forcibly assimilated into Hispanic culture—are still very much alive, whether in Argentina or Chile. Nor have their cultures and languages, though certainly threatened with imminent disappearance after years of being disregarded, been erased from memory.”

Based on this realization, the young researcher’s quest took on an even greater sense of urgency. Supported in her work by the ethnologist and Arctic explorer Jean Malaurie—a legendary figure in the world of extreme adventure—Lauriane multiplied her sound recordings and acoustic tests. On this land now emptied of its first inhabitants, she uncovered forgotten campsites, as well as 2,500 hut locations. She even managed to reconstruct the original Amerindian place names of these sites, which had been replaced by the names given by the Spanish. All this painstaking work now allows Lauriane to suggest that in these ancestral societies, which were entirely oriented toward nature, shamanic chants and rituals were mainly inspired by the sounds made by animals, trees, waves, and winds.

Meeting the Yagans

The ethno-acoustician also set out to meet the last speakers of the Yagan, Haush, and Selknam languages in Argentina and Chile. This brought to life the accounts left by the few anthropologists who, at the start of the last century, took an interest in these Indigenous peoples—such as the missionary Martin Gusinde, who, in the 1920s, quickly set aside his evangelizing mission to immerse himself passionately in the daily life of the tribes. In 2018, during a new journey, Lauriane decided to focus her research precisely on the Yagans studied by Gusinde. This time, her destination was the Beagle Channel (Onashaga in the Yagan language). Unlike the Selknams and Haushs, who were hunter-gatherers, the Yagans lived on the water. They were nomads of the channels, traveling in long canoes and subsisting mainly on shellfish, which, according to old accounts, were harvested from icy depths by nearly naked women divers. The atmosphere changed entirely. This expedition took place in a maritime Tierra del Fuego, livelier and even windier than before, where the Atlantic and Pacific oceans meet head-on, often creating dramatic weather conditions.

A little further south of the Beagle Channel lies Cape Horn, renowned as the “official homeland of seasickness.” Then there are the famous caletas—fjords with spongy shores and trees draped in long strands of lichen, inlets carved out by glaciers thousands of years ago. These labyrinths wind westward, beyond Ushuaia, then along the Pacific coast of Chilean fjords and all the way to the Chiloé Archipelago. “Sailing is the only way if you want to land on the islets and coves scattered everywhere,” Lauriane notes. “My initial idea was to wander by canoe like the Yagans, but technically the expedition was too complex and very risky.” So, she joined a French family as a crew member on a sailboat for a three-month expedition. They stocked up and set sail from Ushuaia, then crossed the closely monitored border waters patrolled by the Chilean navy for a first stop in the world’s southernmost port: Puerto Williams, on Chile’s Navarino Island, a major center of Yagan culture. From there, they headed west, zigzagging through the two arms of the Beagle and exploring the shores on foot to catalog the campsites.

For this journey, the acoustician improved her sound investigation tools: microphones capable of recording in all directions, the latest recorders, meticulous protocols, and… a simple wooden box! Bought at a hardware store in Ushuaia, the object is the size of a shoebox. By tapping on its lid, like a drum, it produces a sharp, loud noise that resonates in the emptiness—perfect for testing the echo of a place and analyzing how sound travels through a given site. Inspired by the protocol developed in 1967 by François Canac (a French scientist who worked notably on the acoustics of Roman amphitheaters), this kind of box test helps better understand sites once occupied by the first inhabitants.

A Crucial Discovery

After leaving the boat, Lauriane returned to the steppes for two more months of solitary research. Then, last April, during her latest expedition, she made her most important discovery in the center of Tierra del Fuego. She headed to the Ewan I site, once used by the Selknam for the Hain initiation ritual for young adults. Studied by the anthropology and archaeology laboratory of Cadic (the Southern Center for Scientific Research in Ushuaia), the site still has a ceremonial hut standing, dated to 1905. “There,” Lauriane recounts, “I was able to carry out acoustic tests to understand the placement of this hut. Located on the edge of an old clearing, Ewan I actually functions like an amphitheater, where sounds (songs, words, cries) are absorbed, conducted, or deflected by the terrain. It is likely that these effects were not accidental but were considered in the choice of the ritual site to ensure the ceremony went smoothly.” This sheds new light on the acoustician’s university thesis. “Tomorrow, we’ll be able to explain other sacred sites by analyzing how they resonate,” she says enthusiastically, already thinking about her next trip. It will be soon, and perhaps aboard her own little sailboat. “I dream of crossing the Atlantic,” confides our Breton. Before once again setting course south, toward that Fuegian land that still has so many sonic nuances to whisper to her.

![[Sailing Patagonian channels] Sébastien’s Logbook part 1](https://karukinka.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Caleta-eva-luna_012025_Karukinka4-400x250.jpg)